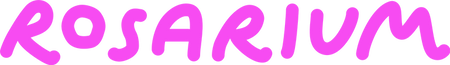

There’s a particular kind of quiet that settles over Ghost Ranch. It’s not silence, exactly - more a stillness that hums beneath everything. When Georgia O’Keeffe first visited in the 1930s, she said the landscape “belonged to me as soon as I saw it.” The red cliffs, the open horizon, the shifting light - all of it gave her something she couldn’t find elsewhere.

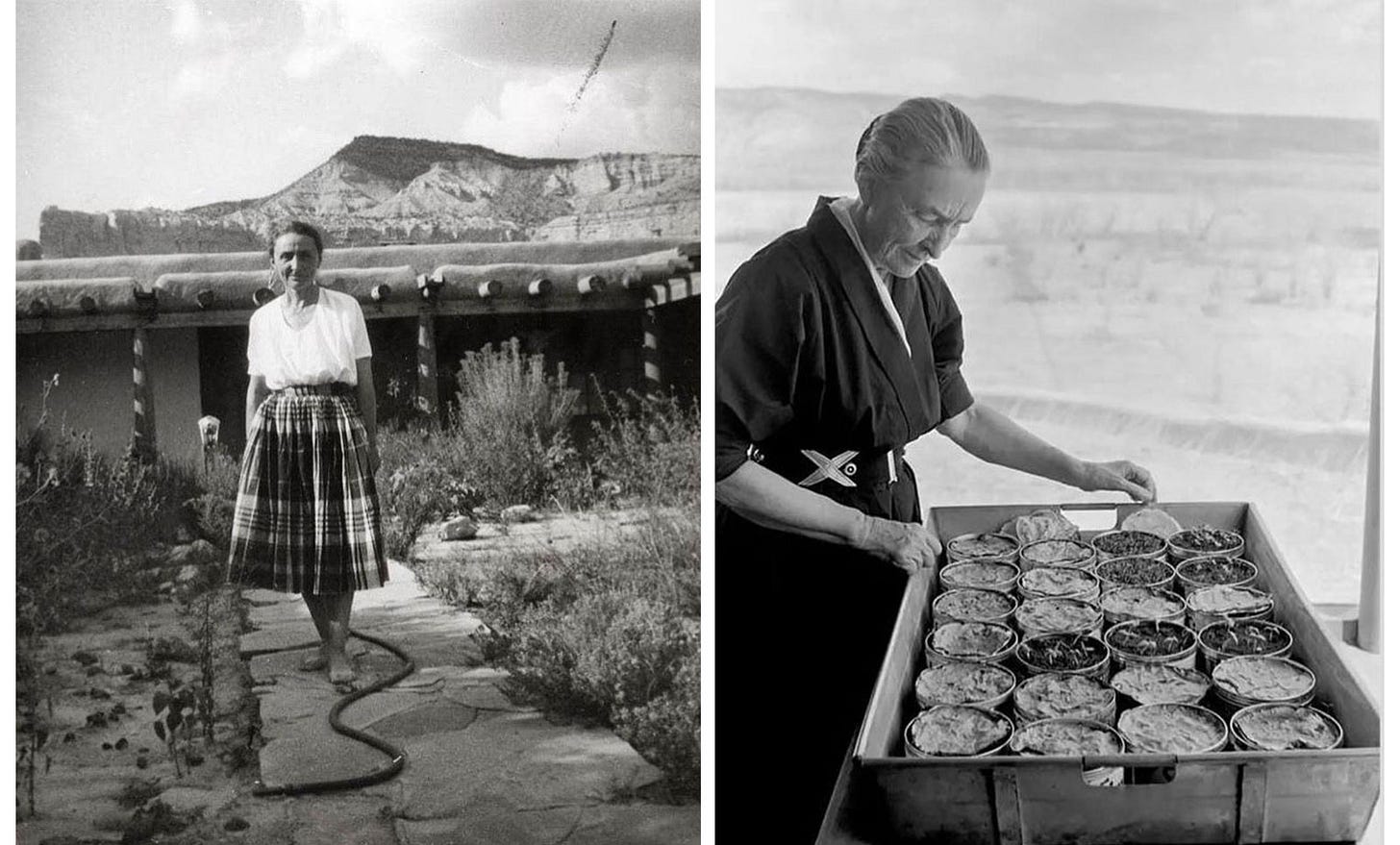

A few years later, she made that feeling permanent. In 1940, she bought a small house at Ghost Ranch, and later another in nearby Abiquiú - a crumbling adobe with a walled garden she painstakingly revived. There, she grew vegetables, herbs, and flowers, bringing them into her kitchen and her canvases. The garden wasn’t separate from her art; it was an extension of it. The same sensitivity that translated bleached bones and canyon walls into abstraction was present in the way she placed a seed in soil. The garden wasn’t a separate practice. It was her studio under open sky.

Every creative practice, I think, begins with the same impulse - to tend, to cultivate, to listen. In the garden, I work with living material that pushes back, that insists on its own pace. In the studio, I work with another kind of living matter: fabric with memory, texture, resistance. Deadstock textiles carry their own history - the traces of what they were meant to become, and what they might still be.

There’s a rhythm that connects the two. The same patience that governs a seedling governs the cut of cloth. The same joy in seeing something thrive in unexpected conditions. O’Keeffe understood that - the way repetition and care become a language of their own.

Georgia O’Keeffe ‘Hollyhock Pink with Pedernal’, 1937, Milwaukee Museum of Art, Milwaukee, Wisconsin

Ghost Ranch wasn’t just a home; it was a deliberate choice. O’Keeffe was captivated by the desert’s extremes - the stretch of horizon, the vivid sky, the way the land changed hour by hour. Here, she could build a life that mirrored her art: disciplined yet alive, minimal yet full of subtle forms. Her garden grew within this clarity, a grounding practice that connected her to the rhythms of the land and fed the work that emerged from her studio.

O’Keeffe’s attention to the details of daily life extended beyond the garden and studio to the way she dressed and arranged her home. Her wardrobe was famously minimal and deliberate: custom wrap dresses in muted colors, carefully selected so that each piece could be worn again and again, allowing her freedom to focus on her work. In photographs of her Abiquiú home, her closets and living spaces reflect the same clarity and restraint as her paintings - ordered, purposeful, and full of subtle beauty. Every object, from her furniture to her clothing, was chosen with intention, a quiet reminder that aesthetic care can permeate all aspects of life, not just the act of making art.

Interiors of Georgia O'Keefe's home at Ghost Ranch

O’Keeffe once said she wanted “to create an equivalent for what I felt about what I was looking at - not copy it.” That’s what the garden gave her - not just subject matter, but a way of being with the world. To plant, to tend, to harvest - all ways of noticing, all ways of translating sensation into form.

In her world, nothing was wasted. Everything found its form again - in color, texture, gesture. That idea sits at the heart of my own work, too. Each collection begins not from blankness but from remnants: discarded fabrics, waiting to be reinterpreted. Like O’Keeffe’s garden, it’s a process of tending and transformation - an ongoing conversation between the hand, the material, and the season.

Maybe that’s the quiet lesson of Ghost Ranch: creation isn’t born from endless newness, but from returning - again and again - to what’s already here, ready to be cultivated.

Leave a comment